The Czechoslovak-Australian Association of Canberra and Region, Inc.

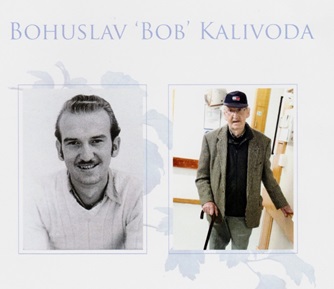

Bohuslav Kalivoda - in memoriam

(7. 12. 1926 – 7. 4. 2014)

7. dubna zemřel ve věku 87 let náš přítel a jeden ze zakládajících členů Besedy Bohuslav Kalivoda. Pohřební obřad se konal v katedrále St. Christopher, Manuka a na hřbitově v Canbeře.

V dalším uvádíme eulogie Aleše Zezulky a Petra Kalivody, které byly předneseny v katedrále. Děkujeme za jejich souhlas se zveřejněním.

Bob byl mimořádný člověk, čeho se chopil, to se mu dařilo, s jeho pílí, energií a talentem byl pro nás příkladem.

Byl jeden z prvních zakladatelů naší Česko-Slovensko/Austrálské Asociace Beseda, psal se rok 1969! Před patnácti lety, s pomocí některých členů Besedy, se podílel na zakoupení objektu, dnešního klubu Beseda.

Byl dobrým obchodníkem, a to se také odrazilo v jeho dlouholeté spolupráci s Besedou jako pokladník.

Byl dobrým kamarádem, rád vypomáhal dobrou radou.

Jak mnozí zajistě víte, Bob obchodoval s vínem, pivem a kořalkou, vlastnil jeden z větších obchodů ve Oaks Estate, Queanbeyan. Proč to říkám: nikdy jsem Boba neviděl pít nadmíru, nepoužíval vulgární slova a nebyl nikdy nahněvaný, což mně mnohokrát bylo příkladem, vážil jsem si ho.

Obdivoval jsem jeho neuhasitelnou žízeň po vědění, byl přímo encyklopedicky vzdělaný, vynikající filatelista.

Budeš nám chybět Bobe, odešel jsi na druhou stranu, avšak zůstaneš v našich srdcích.

Děkujeme Ti Bobe, za tvé přátelstvi a za tvojí práci pro Besedu.í

LIFE IS THE GREATEST GIFT THAT GOD HAS GIVEN US, DEATH IS ONLY A BRIDGE TOWARDS ETERNAL LIFE WITH GOD. CERTAINLY, HEAVEN IS REJOICING FOR ANOTHER SOUL HAS FINALLY REACHED HIS TRUE HOME. AMEN

Thank You Bob

My father, Bohuslav Kalivoda, also known as Bob Kalivoda, was born on the 7th December, 1926 in a small town named Strážov in a part of Czechoslovakia that is now the Czech Republic. Dad’s parents, Jakub and Božena, owned a mixed business that included a grocery store, an inn and a bar. According to Dad, he did quite a few chores to help them. One of them was guarding cherries ripening on trees that grew on public land next to a road and were apparently a big temptation to other local children. Another one of his chores was going out on the street selling the vinegary and spicy water that gherkins and cucumbers were fermented in, which people liked so much that they paid money to drink it by the cupful. Dad had quite a taste for the water himself. One time he drank all of it before he had a chance to sell any of it. Frightened of what his parents would do when he returned home empty handed, he went to the local river and filled the barrel on the small handwagon with fresh water and sold that as if it was vinegary gherkin water. He told me that there weren’t any complaints because nobody seemed to notice that they were drinking pure water.

Dad was thirteen or fourteen years old when Germany invaded Czechoslovakia. So as a teenager in an occupied country, he did not join any Army. Instead, he was very active holding underground meetings with the Boys Scout Movement which being a British institution in direct competition with the Hitler Youth Movement, was banned in German occupied territories. He told me that if the Germans had ever discovered that he was an organiser of Scout meetings, he would have been jailed for sure, or maybe even lined up against a wall and shot.

Dad also learnt how to speak English during the war. There was a shortage of all materials at the time and Dad had to send three plastic records to a factory where the records were melted down and remade into “how to speak English lessons”.

After the war, Dad went into business with his older brother, Ferdinand, manufacturing and selling souvenirs for tourists to buy all over Czechoslovakia. The business was very successful. It employed twenty-five people when the communist took over a few years later and ordered that committees be formed in factories all over the country. In Dad’s factory, the foreman was put in charge of the committee of factory workers. He told Dad and his brother that they could stay on as managers as long as they did what the committee told them to do. Dad considered the man to be a fool. That was when he decided that it was time for him to leave Czechoslovakia.

Mum told me that Dad and she escaped from Czechoslovakia by arranging to be a part of a convoy of timber workers who were allowed to harvest timber in the three kilometre no man’s land before the border with Germany. Anybody else who entered that area was shot on sight by border guards. Mum said that Dad had a revolver in his pocket. Knowing Dad, I don’t think he would have used it, but you never know. Anyway, Mum said that when they left the convoy deep in the forest and started walking towards the German border that Dad walked so fast and made such big steps that she had trouble keeping up with him.

Mum and Dad were married in Germany and they ended up in a refugee camp in Italy where I was born during the following year. Dad, who knew how to speak several languages, got a job assisting the refugee camp manager with office duties and acting as an interpreter. About the same time as I was born, Mum and Dad were given the choice of emigrating to one of two countries, either Chile or Australia but they didn’t know which one to choose. So they asked the refugee camp manager, who was a former sea captain who had been all over the world, for his opinion, and he said, “If you go to Chile, you’ll either be a very rich man or a very poor man for the rest of your life, because there’s nobody in between that in Chile. But if you go to Australia, you won’t be really rich, but you won’t be poor either, because in Australia nobody’s really rich or really poor.” Mum and Dad still didn’t know where to go, so they decided to toss a coin, and, lucky for the whole family, we ended up coming to Australia. And as a by the way, I don’t think Mum or Dad ever tossed a coin for anything after that.

When we arrived in Australia in late 1949, Dad had a contract to work for the Federal Government for two years. It was an experience that put him off working for governments for the rest of his life. That didn’t mean that he didn’t have good memories of those times. In fact, he made quite a few lifelong friends during that time. His first job was as an off-sider or assistant to truck-drivers and various tradesmen, such as carpenters and carpet-layers. One of the stories he liked to tell was how a team of government carpet layers he worked with had to give a quote of the cost before they were given any work to do by their superiors. So, naturally the quote was always a low optimistic one and whenever a job ended up costing more than the amount that had been quoted, the foreman would always say, “Don’t worry about it, we can charge the extra amount to the cost of the carpet in Parliament House,” which apparently was a bottomless pit.

During the time Dad worked for the government, he and Mum purchased a block of land in Blackall Avenue, Queanbeyan, where Dad spent all of the spare hours God gave him building a two bedroom house for us. Not long afterwards, about two and a half years after I was born, my sister Margaret was born in the old Canberra Hospital, and several years later our sister, Karyn, came along as well.

Now, I’m not sure in what order the following happened, but I want to give you some idea of how industrious and hardworking Dad was and to know that he was a man who rarely wasted any minutes during any day. When the house was finished, Dad started working nights selling white goods, door-to-door, on behalf of a local shop, Harris’s Electrical Store. He also started his own business manufacturing Holland blinds in a big shed behind our house. Another task Dad had at the time was interpreting for the police whenever there was a domestic dispute between a couple who couldn’t speak English. He hated doing that, especially after he purchased a grocery shop specialising in European products and the disputing parties were possibly potential customers of his.

At some time during the mid-fifties Mum and Dad abandoned their plans to build a bigger house on the block in Queanbeyan and decided to build a house in Deakin instead. This is the house where Mum and Dad lived for the rest of their lives, almost sixty years. Dad built the house without ever having a mortgage on it and that was seven years after he had arrived in Australia with one American dollar in his pocket. I think that that’s food for thought, these days, when couples have to spend many, many years working to pay off their mortgages.

During the mid-nineteen sixties, Dad started another shop. This time in the Campbell shopping centre. It was a great success both financially and socially. I know that Mum and Dad was well liked by the local people because even these days, some fifty years later, I still bump into old customers from Campbell, from time to time, who invariably tell me that they have very fond memories of the time that Mum and Dad owned that shop.

In the early nineteen seventies, Dad started another business bottling wine from wooden casks into two litre flagons that were distributed to shops and other outlets throughout the ACT and surrounding districts of New South Wales. Over the years that business evolved into a retail outlet and Dad finally retired when we sold the business in 1997, when he was 70 years old.

Besides being in business, Dad had a parallel life as an artist and a painter. During his life he had at least half a dozen art exhibitions, including one in Qantas House in London which was very successful, and a retrospective exhibition in the High Court Building several years ago. The current monthly edition of the Newsletter of the Queanbeyan Art Society, a society of which Dad was a Life Member, describes him as “one of Queanbeyan and region’s best artists”. He also entered many art competitions all over Australia and won quite a few prizes, and for five or six years he judged the art competition at the Royal Canberra Show. Dad always had a dream to take his art much further than he did, but, alas that was not to be.

For Dad, retirement didn’t mean taking it easy by sitting and lolling around the house doing nothing or watching TV. Amongst many other things, he spent his time painting pictures, tending to his vineyard at Ingelara and making wine, being an active member of Queanbeyan West Rotary, being treasurer of Beseda, which is a social and cultural club for Czechs, Slovaks and their friends, attending to his stamp collection and he even found time to do the weekly shopping with Mum and doing some housework for the first time in his life. I remember him saying, one or two years after he retired, that he was so busy nowadays that he wouldn’t have had time to go to work anyway.

Although Dad was, in many ways, European to the marrow of his bones, he did what he could to integrate and be a fair dinkum Ozzie. I think that was why he liked to be called Bob, not Robert, but plain old Bob, which to him was a genuinely Ozzie name. Before he settled on being known as Bob in Australia, he was known by other names. People who worked with him in the government or did business with him in Queanbeyan in the early days during the nineteen fifties always called him Boris. Friends who came to our house at that time and heard Mum call him Boža, which is short for Bohuslav, called him Boža as well. After Dad settled on being known as Bob, he was always very proud of being known by that name. Becoming a member of Rotary was another way of being a fair dinkum Ozzie. He also loved the comraderie amongst the Rotary members and their charitable activities fitted in with Dad’s desire to give something back to the community that had given him so much.

When Dad escaped from the communist regime in Czechoslovakia, he was stripped of his citizenship and became a stateless person. Some years ago, after the communist regime fell, the Czech Ambassador offered to arrange to have Dad’s Czech citizen reinstated, but Dad declined the offer. He felt that he owed his full loyalty to Australia, the country that had helped him when he needed help. Dad also believed that actions speak louder than words, and having his Czech citizenship reinstated was only words, and, in his case, words much too late at that. But that didn’t mean that the country of his youth and where he was born wasn’t one of the most important things in his life. He loved the Czech Republic of his boyhood and youth, and he loved Australia as the place where he had achieved so much.

Dad died of old age and a broken heart for Mum. When Mum was alive, she was always worried about what would happen to Dad if she was the first to pass away, and she was right, Dad genuinely felt that his life was over when Mum passed away in November last year.

Ztráta Kalivodových

Zpráva o úmrtí a pohřbu Bohouše Kalivody přinesla vzpomínky na jeho pomoc a dlouholetou práci ve výboru Besedy. Odešel přítel a kamarád, kterého lze těžko nahradit.

Účast rodiny Kalivodů na založení a budování Besedy bude vždy mimořádnou kapitolou ve vytváření funkčního krajanského sdružení v Canbeře. Osobní zodpovědnost a pracovitost byla znakem Bohouše. Jeho široký okruh příbuzných a známých navíc nabídl řadu dalších obětavých přátel Besedy.

Před několika měsíci odešla navždy jeho manželka Traudi Kalivodová, stálá pomoc všem, kdo ji znal. Veselá a obětavá. Nyní následoval Bohouš. Věk byl na jejich straně, dovolil dlouhý aktivní život a pomoc všem v jejich okolí.

Kalivodovi přišli do Austrálie v padesátých letech, začínali v Queanbeyanu, tedy skoro předměstím Canberry. Začali podnikat, založili obchod s potravinami a delikatesami, později i vínem, který se soustavně zvětšoval pílí obou manželů. V tom období si stavěli dům a narodil se jim syn a dvě dcery. Vznikal také jejich dům v Canberra- Deakin, kde dožili jejich odchodu do odpočinku.

Bohouš byl nadaným umělcem, člen Svazu umělců a výtvarníků v Sydney a dva jeho obrazy jsou v Národní Galerii v Praze. Byl také dlouholetým členem Rotary klubu.

Zůčastnil se s krajany protestu před ruským velvyslanectvím v srpnu 1968 v Canbeře. Tam také vznikla myšlenka založit krajanské sdružení Beseda. Po založení se stal členem výboru Besedy pro kulturu a později pokladníkem.

Jeho stěžejní zásluhou v Besedě je převedení rozpočtu sdružení do úspor, které později umožnily zakoupení budovy Besedy. Jeho neuvěřitelná poctivost a šetrnost i v nejmenších detailech hospodaření, kdy jsme museli podepisovat všechny jeho finanční výkazy, byla zkušeností pro každého z nás.

Vzpomínka na Bohouše a Traudi bude vždy spojena s absolutní integritou jejích personalit k úkolům a sdružení, kterému sloužil desítky let.

Bohouši a Traudi - nezapomeneme.

R.J.

Copyright © 2014 Beseda | All Rights Reserved

Design Miroslav Novak, based on Multiflex template by G. Wolfgang